This is the learning notes of MIT Course 6.006 Introduction to Algorithms.

Introduction to Algorithms

If you want to be a good programmer, you can just program every day for two years, and you'll be an excellent programmer. If you want to be a world-class programmer, you can program every day for ten years, or you can program every day for two years and take an algorithm class.

Charles Leiserson

The analysis of algorithm is the theoretical study of computer program performance and resource usage.

What's more important than performance?

Modularity, Security, Scalability, Simplicity, Robustness, User-friendliness...

Why study algorithms and performance?

Performance measures the line between feasible and the infeasible.

If the program is not fast enough, it's simply not functional.

Algorithms give you a theoretical language for talking about program behavior, which is adopted by all the practitioners.

Performance is like the money in economy. You have to pay some performance for other things like security, user-friendly.

We all like fast games.

Running time

- Depends on input itself. (e.g. already sorted)

- Depends on input size. (e.g. \(6\) elements v.s. \(6 \times 10^9\) elements)

- parameterize the input size to \(n\)

- Want upper bounds of running time

- because it's a guarantee to user. For example, the program would spend 0.3 seconds at most.

Kinds of analysis

Worst-case (usually) \[ T(n) = \text{max time on any input of size $n$} \]

Average-case (sometimes) \[ T(n) = \text{expected time over all inputs of size $n$} \] (Need assumption of statistical distribution of inputs (e.g. uniform distribution), so that we can calculate the \(\mathbb{E}(t)\) of all inputs)

Best-case (bogus, useless, meaningless)

You could cheat by using a slow algorithm with some specific inputs getting pretty good performance, but it's useless.

BIG IDEA of Algorithm Analysis

- Ignore machine dependent conditions

- Look at growth of \(T(n)\) as \(n \to \infty\)

Asymptotic Notations

\(\mathbb{O}\)-notation

Demonstrates the upper bound of time running an algorithm.

\(f(n) = \mathbb{O}(g(n))\) means there are some suitable constants \(c>0\) and $n_0 > 0 $, such that \(0 \le f(n) \le c\cdot g(n)\) for all \(n \ge n_0\).

Ex: \(2n^2 = \mathbb{O}(n^3)\)

Set definition: \(\mathbb{O}(g(n))= f(n):\) there are some constants \(c>0\) and \(n_0>0\), such that \(0 \le f(n) \le c \cdot g(n)\) for all \(n \ge n_0\).

Ex: \(f(n) = n^3 + \mathbb{O}(n^2)\) means there is a function \(h(n) \in \mathbb{O}(n^2)\), such that \(f(n) = n^3 + h(n)\). This \(h(n)\) is also considered the error term.

Ex: \(n^2 + \mathbb{O}(n) = \mathbb{O}(n^2)\) means for any \(f(n) \in \mathbb{O}(n)\), there is an \(h(n) \in \mathbb{O}(n^2)\), such that $ n^2 + f(n) = h(n)$.

\(\Omega\)-notation

Demonstrate the lower-bound of time running an algorithm.

Definition: \(\Omega(g(n))=f(n):\) there exist \(c>0\) and \(n_0>0\), such that \(0 \le c \cdot g(n) \le f(n)\) for all \(n \ge n_0\).

Ex: \(\sqrt{n} = \Omega(\lg n)\)

\(\Theta\)-notation

In Engineering

\(\Theta\)-notation: Drop low-order terms, Ignore leading constants.

Ex: \(3n^3+90n^2-5n+6046 = \mathbb{\Theta}(n^3)\)

As \(n \to \infty\), \(\mathbb{\Theta}(n^2)\) algorithm always beats the \(\mathbb{\Theta}(n^3)\) algorithm.

In Mathematics

Definition: \(f(n) = \Theta(g(n))\) means there are some suitable constants \(c_1>0, c_2>0\) and $n_0 > 0 $, such that \(c_1 \cdot g(n) \le f(n) \le c_2 \cdot g(n)\) for all \(n \ge n_0\).

In other words, \(\Theta(g(n)) = \mathbb{O}(g(n)) \cap \Omega(g(n))\).

Ex: \(n^3+2n^2 = \Theta(n^3) = \mathbb{O}(n^4) = \mathbb{O}(n^3) = \Omega(n^2) = \Omega(n)\)

Other Notations

- \(o\)-notation: >

- \(\omega\)-notation: <

Ex: \(2n^2 = o(n^3) = \omega(n)\)

Solving Recurrences

There are 3 main methods to solve recurrences, which are substitution method, recursion-tree method and master method. Usually, we solve recurrences applying recursion-tree method or master method, and validate the result using substitution method.

Substitution Method

- Guess the form of the solution.

- Verify by induction.

- Solve for constants.

Recursion-tree Method

Always useful but a little bit non-rigorous.

Ex: \(T(n) = T(n/4) + T(n/2) + n^2\)

Master Method

Applies to recurrences of the form \(T(n) = aT(n/b) + f(n)\), where \(a \ge 1\), \(b > 1\), \(f(n)\)should be asymptotically positive.

The recurrence satisfied: \[ T(n) \le \begin{cases} constant & \text{for small $n$} \\ aT(n/b) + \Theta(n^d) & \text{for general $n$} \end{cases} \]

- \(a\) —— number of sub-problems

- \(b\) —— decay coefficient of the sub-problem

- \(d\) —— coefficient related to merge the sub-problems

- \(a, b, d\) is independent from \(n\)

In this case, according to master method, the time complexity of recurrence is as follows: \[ T(n) = \begin{cases} \Theta(n^d) & \text{if $a < b^d$, case 1} \\ \Theta(n^d\log n) & \text{if $a = b^d$, case 2} \\ \Theta(n^{\log_ba}) & \text{if $a > b^d$, case 3} \end{cases} \]

Ex: \(T(n)=9T(n/3) + n\) \[ \begin{split} &\because a=9, b=3, d=1 \\ &\therefore a=9 > b^d=3 \\ &\therefore T(n) = \Theta(n^{\log_b a}) = \Theta(n^2) \end{split} \] Ex: \(T(n) = T(2n/3) + 1\) \[ \begin{split} &\because a=1, b=\frac{2}{3}, d=0 \\ &\therefore a=1 = b^d=\left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^0 \\ &\therefore T(n) = \Theta(n^d \log n) = \Theta(\log n) \end{split} \] Ex: \(T(n) = 3T(n/4) + n \log n\) \[ \begin{split} &\because n^d = n \log n, n < n \log n < n^2 \\ &\therefore n < n^d < n^2 \\ &\therefore 1 < d <2 \\ &\therefore 4 < b^d < 16 \\ &\therefore a = 3 < b^d \\ &\therefore T(n) = \Theta(n^d) = \Theta(n\log n) \end{split} \] Ex: \(T(n) = 2T(n/2) + n\log n\) \[ \begin{split} &\because n^d = n \log n, n < n\log n < n^2 \\ &\therefore n < n^d < n^2 \\ &\therefore 1 < d < 2 \\ &\therefore 2 < b^d < 4 \\ \end{split} \] Given that \(a=3\), we cannot tell \(a\) is larger than \(b^d\), or \(b^d\) is larger than \(a\). Therefore, we cannot apply the master method in this case.

Problem: Sorting

Input: sequence \(<a_1, a_2, \cdots, a_n>\) of numbers

Output: permutation (rearrangement) of \(<a_1', a_2',\cdots,a_n'>\) to make: \[ a_1' \le a_2' \le \cdots \le a_n' \]

Sorting Model

Comparison Sorting Model

Comparison sorting model is that only use comparisons (\(<, \le, =, \ge, >\)) to determine the relevant order of elements.

Theorem

No comparison sorting algorithm runs better than \(\Theta(n \log n)\).

Non-comparison Sorting Model

Assume they are integers in a particular range. There are two algorithms here that's faster than \(\Theta(n \log n)\), counting sort and radix sort, which are \(\mathbb{O}(n)\). These sorting algorithm could be seen in Chapter Sorting.

Insertion Sort

Pseudo Code

1 | Insertion-Sort(A, n) //Sort A[1,...,n] |

Explanation

The core of this algorithm is to take out the key element from the array, compare it with it's former elements until it's correctly ordered, and then insert the key element to that place.

- Animation

Animation explanation of insertion algorithm

- Diagram

Diagram of insertion algorithm

Insertion Sort Analysis

Worst case: input reverse sorted array \[ T(n) = \sum_{j=2}^{n}{\Theta(j)} = \Theta(n^2) \]

Is insertion sort fast?

- Moderately fast for small \(n\)

- Not at all for large \(n\)

Merge Sort

Explanation

Given an unsorted list \(A[1 ... n]\)

If \(n = 1\), done —— \(\Theta(1)\)

Recursively sort \(A[1 ... n/2]\) and \(A[n/2+1 ... n]\) —— \(2T(n/2)\)

Merge 2 sorted lists —— \(\Theta(n)\)

Ex: merge the following sorted subsequences:

1 5 9 13

2 6 8 11

Compare the heads of 2 sequences, take away the smaller one and move the header (pointer) to the next element, and you will get:

1 2 5 6 8 9 11 15

Code in Python:

1 | def MergeSort(A): |

Analysis of Merge Sort

From the Explanation, we can get: \[ T(n) = \cases{ \Theta(1) & $n=1$ \\ 2 T(n/2) + \Theta(n) & $n \neq 1$ } \] Because \(n=1\) is not so meaningful in engineering, so the case of \(n=1\) is usually omitted, and \(T(n)\) is as follows: \[ T(n) = 2T(n/2) + \Theta(n) \] This recurrence could be solved by using Master Method. \[ \begin{split} &\because a = 2, b = 2, d = 1 \\ &\therefore a = 2 = b^d \\ &\therefore T(n) = \Theta(n^d\log n) = \Theta(n \log n) \end{split} \]

\(\Theta(n \log n)\) is faster than \(\Theta(n^2)\). Actually merge sort is faster than insertion sort when \(n\) is bigger than 30 or so.

Quicksort

Quicksort was invented by Tony Hoare in 1962.

- It's a Divide and conquer algorithm

- It sorts "in place"

- Very practical (with tuning)

Divide and conquer

- Divide: Partition array into 2 subarrays around pivot \(x\), such that elements in lower subarray \(\le x \le\) elements in upper subarray.

- Conquer: Recursively partition 2 subarrays.

- Combine: Trivial.

Pseudo Code

Partition

1 | Partition(A, start, end) // A[start...end] |

Diagram explanation of partition

- \(pivot\) means the pivot element.

- \(i\) means the pointer pointing the boundary of the lower subarray, and the index of \(pivot\) in the end.

- \(j\) means the pointer pointing boundary of the upper subarray.

The time complexity of "Patition" is \(\Theta(n)\), because you just go through the array once, compare each element with the pivot and put the element in the right zone.

QuickSort

1 | QuickSort(A, left, right) |

Animation Explanation

Animation explanation of quick sort algorithm.

Partition the array into left and right, two subarrays.

Recursively partition the left subarray and the right subarray.

(Explained the same in the "Divide and Conquer" of this section)

Analysis of Quicksort Algorithm

Worst case time

If we are unlucky, which means to consider the worst case of the quicksort:

- input sorted or reverse sorted

- one side of partition has no elements

\[ \begin{align} T(n) & = T(0) + T(n-1) + \Theta(n) \nonumber\\ & = \Theta(1) + T(n-1) + \Theta(n) \\ & = T(n-1) + \Theta(n) \nonumber\\ \end{align} \]

By applying Recursive Tree Method, we could solve this recurrence to be: \[ T(n) = \Theta(n^2) \]

Best case time (for intuition only)

If we are really lucky, Partition splits the array \(n/2 : n/2\). \[ T(n) = 2T(n/2) + \Theta(n) = \Theta(n \log n) \]

Average case time

Suppose we alternate lucky, unlucky, lucky, ... , the recurrence would be: \[ \begin{align} & L(n) = 2U(n/2) + \Theta(n) & \text{(lucky)} \label{lucky}\\ & U(n) = L(n-1) + \Theta(n) & \text{(unlucky)} \label{unlucky} \end{align} \] Then substitute (\(\ref{unlucky}\)) into (\(\ref{lucky}\)), we get: \[ \begin{align} L(n) & = 2[L(n/2-1)+\Theta(n/2)] + \Theta(n) \nonumber\\ & = 2L(n/2-1) + 2\Theta(n) \nonumber\\ & = 2L(n/2) + \Theta(n) \\ & = \Theta(n \log n) \nonumber \end{align} \] So we are lucky in this case.

Randomized Quicksort

Choose a random pivot or randomly shuffle the input to avoid the worst case.

Advantages

running time is independent from input ordering

no assumptions about input distribution

no specific input can elicit the worst behaviour

The worst case is determined only by the random number generator, rather than the input distribution.

Analysis

\(T(n) = r.v\) for running time assuming random numbers are independent.

For \(k=0,1, \cdots, n-1\), let \[ X_k = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if partition generates a $k:n-k-1$ split} \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \]

\(X_k\) is an indicator random variable (\(r.v\)).

\[ \begin{align} \mathbb{E}[X_k] & = 0 \times P\{X_k=0\} + 1\times P\{X_k=1\} \nonumber\\ & = P\{X_k=1\} \\ & = 1/n \nonumber \end{align} \]

\[ \begin{align} T(n) & = \begin{cases} T(0) + T(n-1) + \Theta(n) & \text{if $0:n-1$ split} \\ T(1) + T(n-2) + \Theta(n) & \text{if $1:n-2$ split} \\ \cdots \cdots \\ T(n-1) + T(0) + \Theta(n) & \text{if $n-1:0$ split} \\ \end{cases} \nonumber\\ & = \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}X_k(T(k)+T(n-k-1)+\Theta(n)) \nonumber \end{align} \]

\[ \begin{align} \mathbb{E}[T(n)] & = \mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{k=0}^{n-1}X_k(T(k)+T(n-k-1)+\Theta(n))\right] \nonumber\\ & = \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}\mathbb{E}[X_k(T(k)+T(n-k-1)+\Theta(n))] \nonumber\\ & = \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}\mathbb{E}[X_k] \cdot \mathbb{E}[(T(k)+T(n-k-1)+\Theta(n))] \nonumber\\ & = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}\mathbb{E}[(T(k)] + \frac{1}{n} \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}\mathbb{E}[(T(n-k-1)] + \frac{1}{n} \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}\Theta(n) \nonumber \\ & = \frac{2}{n} \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}\mathbb{E}[(T(k)] + \Theta(n) \nonumber \\ \end{align} \]

Absorb \(k=0,1\) terms into \(\Theta(n)\) for technical convenience. \[ \mathbb{E}[T(n)] = \frac{2}{n} \sum_{k=2}^{n-1}\mathbb{E}[(T(k)] + \Theta(n) \\ \] Applying Substitution Method, $[T(n)] = n n $.

Typically, randomized quicksort is about 3 times faster than merge sort.

Pseudo code

1 | Partition(A, start, end) // A[start...end] |

Heapsort

Algorithm

- Build a max heap based on the given list.

- Take the root node and swap the first element (root node) of the list with the final element (last leaf).

- Decrease the range of the list by one.

- Heapify the new first element (root node).

- Go to step 2 unless the considered range of the list is one element.

Explanation

Animation

A run of heapsort sorting an array of randomly permuted values

Code in Python

Basic knowledge of a heap

A heap is a complete binary tree, which could map its relevant list. Given a list with index started from 0, the indexes of the \(i\) node's left child, right child and parent nodes are: \[ \begin{cases} left(i) = 2(i+1)-1 \\ right(i) = 2(i+1) \\ parent(i) = floor((i-1)/2) \\ \end{cases} \]

1 | def left(i): |

Max heapify

- Compare the root node with its left child and right child, and find the largest node. (need to make sure if the left child or right child exists)

- If the largest node is not the root node:

- Swap the root node and the largest node (left child or right child)

- Let the largest node be the new root and recursively run this function .

1 | def max_heapify(A, i): |

Build max heap

To build a max heap, a binary tree should run max_heapify() from its last parent node to the root node, which is called Bottom-up Build Max Heap.

1 | def build_max_heap(A): |

Heapsort

The algorithm is shown in Algorithm.

1 | def heapsort(A): |

Analysis of the Heapsort

Time complexity of building a max heap

Given that building a max heap step is the bottom-up, the nodes in the second last layer compare once; the nodes in the third last layer compare twice; ... ; the root node compares \(\log n\) times. So the time complexity is that: \[ T(n) = \sum_{k=0}^{\log n} \frac{n}{2^k}k \label{T_heapsort} \] where \(\frac{n}{2^k}\) is the number of nodes in \(k\) last layer.

\(k\) means that there needs \(k\) comparisons in \(k\) last layer.

As \(n \to \infty\), this time complexity could be approximated as: \[ T(n) \approx \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{n}{2^k}k = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{k}{2^k}n \] According to the nature of series that \[ \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} k \cdot x^k = \frac{x}{(1-x)^2} \] the time complexity is now as: \[ T(n) \approx \frac{2}{(1-2)^2} \cdot n = 2n = \Theta(n) \]

Time complexity of latter part in heapsort

Given that this algorithm calls the max_heapify() of root node for \(n-1\) times, and the time complexity of max_heapify(root) is \(\Theta(\log n)\), the time complexity of latter part in heapsort is \(\Theta(n \log n)\).

Time complexity of whole algorithm

\[ \begin{align} T(n) & = \Theta(n) + \Theta(n \log n) \nonumber\\ & = \Theta(n \log n) \nonumber \end{align} \]

The time complexity of heap algorithm is \(\Theta(n \log n)\).

Counting Sort

Notations

- Input: \(A[1, \cdots, n]\), each \(A[i] \in \{ 1, 2, 3, \cdots, k\}\)

- Output: \(B[1, \cdots, n]\) = sorting of \(A\)

- Auxiliary storage: \(C[1, \cdots , k]\)

Pseudo Code

1 | CountingSort(A): |

Explanation

- The first step is the initialization for the counter \(C[i]\). \(C[i]\)s are going to count occurrences of values, so to initialize them to be \(0\)s.

- Increment the counter \(C[i]\) for that value \(A[j]\). So the \(C[i]\) will give us the number of elements in \(A[j]\) that equal to \(i\).

- The prefix sums (accumulate the \(C[i]\)) will make it that \(C[i]\) will give us the number of elements in \(A[j]\) that less than or equal to \(i\).

- Distribution step.

Example: Sort \(A = [4, 1, 3, 4, 3]\) using counting sort algorithm

Initialization: \(C = [0, 0, 0, 0]\)

Increment the counter: \(C = [1, 0, 2, 2]\)

The prefix sums: \(C' = [1, 1, 3, 5]\)

Distribution: \(j\) from \(n\) to 1

\(A[j] = A[n] = 3\). \(C[A[j]] = C[3] = 3\), which means there are 3 elements in \(A\) that are less than or equal to \(A[j]\). So the \(A[j]\) should be put in the 3th place in the sorted list \(B\), which is \(B[C[A[j]]] = B[3] = A[j]\). Then decreasing the counter of \(A[j]\) by 1, which is \(C[A[j]] = C[A[j]] - 1\).

The rest steps are similar, then we get: \(B = [1, 3, 3, 4, 4]\).

Anaylysis

The time complexity of this algorithm is \(\mathbb{O}(k+n)\). \[ T(n) = \begin{cases} \mathbb{O}(n) & \text{if $k = \mathbb{O}(n)$ } \\ \mathbb{O}(k) & \text{if $k \ge \mathbb{O}(n)$} \\ \end{cases} \]

Note that there are two assumptions made to achieve the \(\mathbb{O}(n)\) time complexity:

- All the number are integers.

- The range of the integers is pretty small.

Actually in practice, counting sort is not very good on a cashe though it costs linear time, so counting sort or radix sort is not that fast an algorithm unless your numbers are really small. Something like quicksort can do better.

This algorithm is a stable sort.

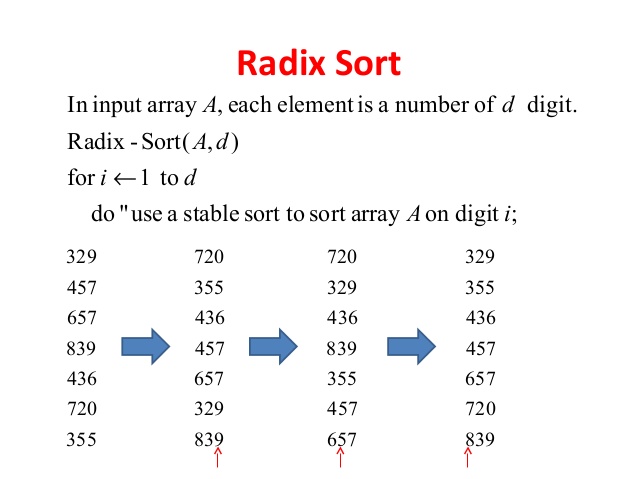

Radix Sort

Radix sort is going to work for a much larger range of numbers in linear time. It sorts data with integer keys by grouping keys by the individual digits which share the same significant position.

A positional notation is required, but because integers can represent strings of characters (e.g., names or dates) and specially formatted floating point numbers, radix sort is not limited to integers.

Radix sorts can be implemented to start at either the least significant digist (LSD) or the most siginificant digit (MSD).

Least significant digit (LSD)

LSD radix sorts typically use the following sorting order: short keys come before longer keys, and then keys of the same length are sorted using stable sort (here is counting sort).

Explanation of LSD

Pseudo Code

1 | RadixSort(A, d): |

Analysis of LSD

- Use counting sort in each round, which means \(\mathbb{O}(k+n)\) in each round.

- Suppose we have \(n\) integers (binary intergers), and each integer has \(b\) digits. (Range of intergers would be \((0,2^b-1)\))

- If we take each digit as a round, the whole complexity would be \(\mathbb{O}(b \times n)\). If \(b\) is constant, it would be fine, but in general, \(b\) is \(\mathbb{O}(\log n)\) (e.g., 1000 (the binary format of 8) has \(b=4\) digits, which means \(b=\log_2 8+1\)), so the whole complexity is \(\mathbb{O}(n \log n)\).

- Split the interger into \(b/r\) digits with each \(r\) bits long, so the there are \(b/r\) rounds, and range of each round is \((0, 2^r-1)\).

Most significant digit (MSD)

PASS

Problem: Order Statistics

Given \(n\) elements in an array, find \(k\)th smallest element (the element of rank \(k\)).

Rand-Select Algorithm

This algorithm is a Randomized Divide and Conquer Algorithm, and is expected-case linear-time order statistics.

Pseudo Code

1 | RandSelect(A, p, q, i): |

Animation Explanation

Animation of Random Selection Algorithm

Analysis of Rand-Select Algorithm

Assuming elements in the array are distinct.

Lucky Case

If the array is divided into \(1/10\) and \(9/10\) in each partition (actually could be any constant ratio), the time comlexity is as following: \[ T(n) \le T\left(\frac{9}{10} n\right) + \Theta(n) = \Theta(n) \]

The recurrence could be solved using master method.

Unlucky Case

If the array is divided into \(1\) and \(n-1\) in each partition, the time complexity is as following: \[ T(n) \le T(n-1) + \Theta(n) = \Theta(n^2) \]

Expected Case

By adopting a similar analysis in Analysis in Randomized Quicksort, we get: \[ \mathbb{E}(T(n)) = \Theta(n) \]

Worst-case linear-time order statistics

The idea of this algorithm is to generate the pivot recursively. Specifically, we would recursively find the median of the array in linear time, and use it as the pivot to find the \(i\)th smallest element using Rand-Select Algorithm.

Algorithm

\(\text{Select}(i, n)\):

Divide the \(n\) elements into \(\lfloor n/5 \rfloor\) groups of \(5\) elements each. Find the medium of each group (\(\Theta(n)\)).

Recursively select the median \(x\) of the \(\lfloor n/5 \rfloor\) group medians.

Partition with \(x\) as pivot, and let \(k = rank(x)\).

if \(i=k\), then return \(x\)

if \(i < k\),

- then return recursively Select \(i\)th smallest element in the lower part of the array.

- else return recursively Select \((i-k)\)th smallest element in the upper part of the array.

Analysis

The time comlexity of this algorithm is \(\Theta(n)\).

Problem: Hashing

Symbol-table Problem

Table \(S\) holding \(n\) records.

Table S holding n records.

Operations

Insert(\(S, x\)) : \(S \gets S \bigcup \{x\}\)

Delete(\(S, x\)): \(S \gets S - \{x\}\)

Search(\(S, k\)): return \(x\), such that the key of \(x\) is equal to \(k\)

return Null if there is no such \(x\)

“Insert” and “Delete” make it a dynamic set.

Direct-access Table

Suppose keys are drawn from \(u = \{0, 1, \cdots, m-1\}\), and assume that keys are distinct.

Set up array \(T[0, \cdots, m-1]\) to represent the dynamic set \(S\), such that \[ T[k] = \begin{cases} x & \text{if } x \in S \text{ and key[$x$]}=k \\ \text{Null} & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \] All operations take \(\Theta(1)\) time.

The main problem of direct-access table is that if there are not many data in this table, the table would have so many empty elements (Null). For example, a 64-bits direct-access table would have \(2^{64}\) keys position to store data, but actually there may be only 1000 samples, costing huge waste of space.

Then, hashing table is a method to avoid this.

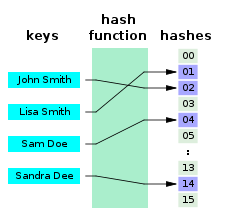

Hashing

Hashing is to use a function \(H\) which maps the keys “randomly” into slots of table \(T\). (Here we call each of the array indexes a slot.)

The principle of Hashing.

When a record to be inserted maps to an already occupied slot, a collision occurs. There are several ways below could solve it.

Choosing a Hash Function

The requirements of a good hash function are as follows:

- Satisfies (approximately) the assumption of simple uniform hashing: each key is equally likely to hash to any of the \(m\) slots. The hash function shouldn’t bias towards particular slots

- Does not hash similar keys to the same splot (e.g. compiler’s symbol table shouldn’t hash variables

iandjto the same slot since they are used in conjunction a lot) - A good hash function is quick to calculate, and should have \(\Theta(1)\) runtime.

- A good hash function is deterministic. \(h(k)\) should always return the same value for a given \(k\).

Division Method

\[ h(k) = k \text{ mod } m \]

\(h(k)\) could map the universe of keys to a slot using it.

\(m\) should not be a power of 2 or 10. If \(m = 2^p\) or \(10^p\), then the \(h(k)\) only looks at the \(p\) lower bits of k, completely ignoring the rest of the bits in \(k\).

e.g. \(k = 11000010100010\), which is a binary number. and \(m = 2^6\), then \(h(k) = k \text{ mod } m = 100010\), which is the 6 lower bits of \(k\).

\(k = 123456789\) and \(m = 10^3\), then \(h(k) = k \text{ mod } m = 789\), which is the 3 lower bits of \(k\).

They all ignore the rest of the bits in \(k\).

A good choice for \(m\) with the division method is a prime number, not too close to a power of 2 or 10.

Multiplication Method

\[ h(k) = \lfloor m(k A \text{ mod } 1) \rfloor \]

- where \(0 < A < 1\) and \((kA \text{ mod } 1)\) refers to the fractional part of \(kA\). Since \(0 < (kA \text{ mod } 1) < 1\), the range of \(h(k)\) is from \(0\) to \(m\).

- The advantage of the multiplication method is it works equally well with any size \(m\).

- \(A\) should be chosen carefully.

- Rational numbers should not be chosen for \(A\).

- A good choice for \(A\) is \(\frac{\sqrt{5}-1}{2}\).

- Faster than Division Method.

Resolving Collisions in Hashing

By Chaining

The idea is to link collision records in the same slot into a linked list.

Resolving collision by chaining.

Analysis

Worst-case: All the keys hash to the same slot, so there is altogether one long linked list.

- Access data takes \(\Theta(n)\) time.

Average-case: Adopting the assumption of simple uniform hashing, which means each key \(k \in S\) is equally likely to be hashed to any slot in \(T\), independent of where other records, other keys are hashed.

Def. The load factor of a hash table with \(n\) keys and \(m\) slots is \(\alpha = n / m = \text{average num. keys per slot}\) .

Expected unsucessful search time: Time to search an element doesn’t exist in hash table. \[ T = \Theta(1 + \alpha) \] where \(\Theta(1)\) is to hash and access the corresponding slot, and \(\Theta(\alpha)\) is to search the element wanted in that slot. (Because the average number of keys per slot is \(\alpha\), and the slot is the structure of linked list, the time to search an element in a linked list is \(\Theta(\text{length of linked list}) = \Theta(\alpha)\)).

Expected search time = \(\Theta(1)\) if \(\alpha = \Theta(1)\), or equivalently \(n = \Theta(m)\).

Expeted successful search time: Time to search an element which exists in the hash table is also \(\Theta(1+ \alpha)\).

The reason why hashing table is so popular is that the operations of it (e.g., insertion, deletion, searching) takes \(\Theta(1)\) time, if the number of slots \(m\) in hasing table is not too small compared to the number of keys \(n\).

By Open Addressing

Resolving collisions by open addressing has no requirement for links. The key idea of it is to probe table systematically until an empty slot is found. \[ \begin{align} & h: U \times \{0,1, \cdots, m-1 \} \to \{ 0, 1, \cdots, m-1 \} \\ \end{align} \] where \(U\) is the universe of keys, the first \(\{0,1,\cdots,m-1\}\) is the probe number, and the second \(\{0,1,\cdots,m-1\}\) is the slot.

- For each key \(k\), there exists a probe sequence:

\[ < h(k, p_0), h(k, p_1), \cdots, h(k, p_i) > \]

where \(p_0, p_1, \cdots , p_i\) are the probe numbers for each hashing, and there are \(i\) steps for finding an empty slot.

- Probe sequence should be permutation. In other words, it should just be the numbers from \(0\) to \(m-1\) in some random order (rearranged).

- Given that the hashing table may fill up, the number of the slots \(m\) must be bigger than the number of keys \(n\), which is \(n \le m\).

- Deletion is difficult.

Ex: Insert \(k = 496\), then the probe sequence could be: \[ < h(496. 6), h(496,1), h(496, 2) > \nonumber \]

- Searching is using the same probe sequence as insertion.

- If it’s successful, it finds the record.

- If it’s unsuccessful, it finds the Null.

Probing Strategies

Linear Probing —— \(h(k, i) = (h(k, 0) + i) \text{ mod } m\)

Key idea:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7i = 0

slot = (h(k,0) + i) % m # here slot = h(k,0)

while slot is full:

i += 1

slot = (h(k,0) + i) % m

if slot is empty:

probe endsKey problem: “Primary Clustering”, which is some regions of the hash table get very full. Then, anything that hashes into that region has to look through all the slots there.

Double Hashing —— \(h(k, i) = (h_1(k) + i \times h_2(k)) \text{ mod } m\)

Key idea:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7i = 0

slot = (h1(k) + i*h2(k)) % m # here slot = h1(k)

while slot is full:

i += 1

slot = (h1(k) + i*h2(k)) % m

if slot is empty:

probe endsThis is an excellent method.

Usually pick \(m=2^r\) and \(h_2(k)\) should be odd.

Analysis of Open Addressing

Assumption of uniform hashing

Each key is equally likely to have any one of the \(m!\) permutations as its probe sequence, independent of other keys.

Theorem \[ \begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\text{num. of probes}\right] \le \frac{1}{1-\alpha} \nonumber\\ \text{if $\alpha < 1$, (i.e, $n < m$) } \nonumber \end{align} \]

where \(\alpha = n/m\), which is the load factor.

If \(\alpha < 1\) as a constant, then probing takes \(\Theta(1)\) time.

For example,

Hashing table is 50% full $ = 2 $ probes;

Hashing table is 90% full $ = 10 $ probes.

Weakness of Hashing

For any choice of hash function, there always exists some bad sets of keys that all hash to the same slot.

To overcome this, one way is to choose hash function randomly, which is called Universal Hashing.

Universal Hashing

Def. Let \(U\) be a universe of keys, and let \(H\) be a finite collection of hash functions, mapping \(U\) to slots \(\{0,1,\cdots,m-1\}\).

We say \(H\) is universal, if \(\forall x, y \in U\), where \(x \neq y\). Then the following is true. \[ |\{h \in H: h(x) = h(y)\}| = \frac{|H|}{m} \] which means that if a hash function \(h\) is chosen randomly from \(H\), the probability of collision between \(x\) and \(y\) is \(1/m\). So that if there are \(|H|\) hash functions to make \(h(x) = h(y)\), the probability of collision between \(x\) and \(y\) for all hash functions in \(H\) is \(\frac{|H|}{m}\).

Algorithm Design

Divide and Conquer

- Divide the problem (instance) into one or more subproblems.

- Conquer each subproblem recursively.

- Combine solutions to the whole problem.

Example 1: Binary Search

The goal is to find \(x\) in a sorted array.

- Divide: compare \(x\) with the middle element in the sorted array.

- Conquer: recurse in one subarray

- Combine: don't do anything.

The time complexity is \(T(n) = 1 \cdot T(n/2) + \Theta(1)\). By applying Master Method, the time complexity is solved to be \(\Theta(\log n)\).

Example 2: Powering a number

Given a number \(x\) and an integer \(n \ge 0\), compute \(x^n\). \[ x^n = \begin{cases} x^{n/2} \cdot x^{n/2} & \text{if $n$ is even} \\ x^{\frac{n-1}{2}} \cdot x^{\frac{n-1}{2}} \cdot x & \text{if $n$ is odd} \end{cases} \label{power} \] The time complexity is \(T(n) = T(n/2) + \Theta(1)\). By applying Master Method, the time comlexity is solved to be \(\Theta(\log n)\).

Example 3: Fibonacci number

\[ F_n = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if $n=0$} \\ 1 & \text{if $n=1$} \\ F_{n-1} + F_{n-2} & \text{if $n \ge 2$} \end{cases} \label{fib} \]

Naive recursive algorithm

Just directly using the recursive formula in \((\ref{fib}\)).

Time complexity: \(\Omega(\psi^n)\), where \(\psi = \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\) (the golden ratio). This costs exponential time, which means it will spend a long time.

Exponential time is bad, polynomial time is good.

Bottom-up algorithm

Compute for \(F_1, F_2, F_3, \cdots, F_n\) one by one:

Time complexity: \(\Theta(n)\)

Naive recursive squaring algorithm

\(F_n = \frac{\psi^n}{\sqrt{5}}\) rounded to its nearest integer, where \(\psi = \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\) (the golden ratio). Given that the \(\psi^n\) will cost \(\Theta(\log n)\) time by using (\(\ref{power}\)), this algorithm's time complexity is also \(\Theta(\log n)\).

Recursive squaring algorithm

Theorem: \[ \begin{align} \begin{pmatrix} F_{n+1} & F_{n} \\ F_{n} & F_{n-1} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} ^n \end{align} \label{fib_matrix} \]

The fibonacci number is solved by (\(\ref{fib_matrix}\)), which spends \(\Theta(\log n )\) time for powering the \(2 \times 2\) matrix (each multiplication of a \(2 \times 2\) matrix costs the constant time).